The study of algorithmic justice emerged in 2011 with Cynthia Dwork [1], who based it on the principle of equal opportunity: all people, regardless of their characteristics, should be able to access the same opportunities and benefits. From that moment on, the study of algorithmic fairness began to gain popularity, to identify and mitigate discriminatory problems in machine learning models.

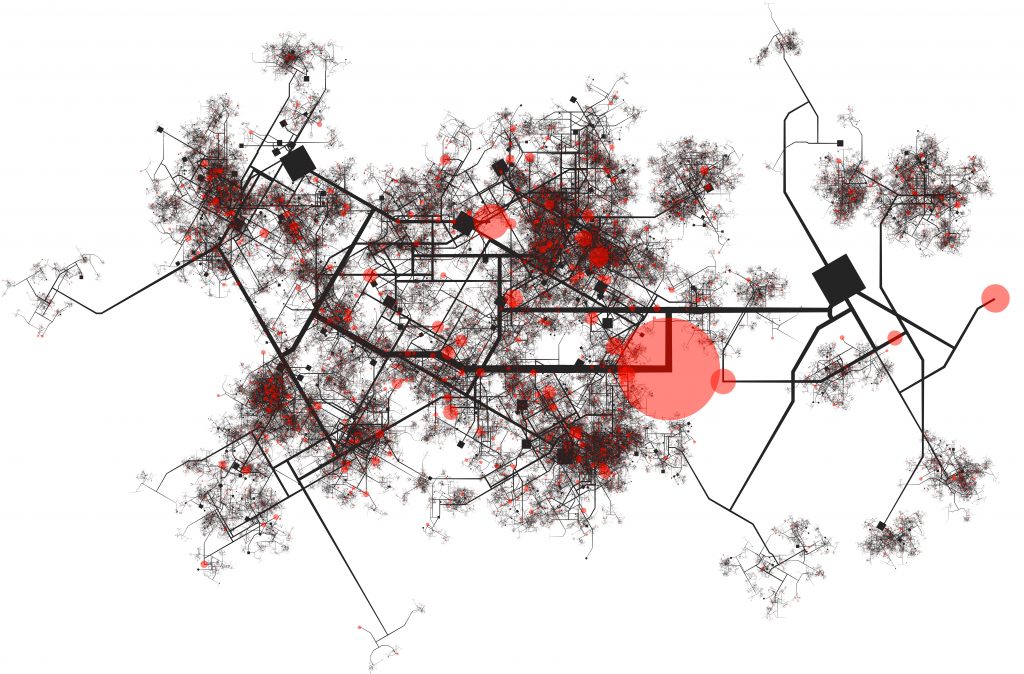

Of particular concern are the biases that may be present in crime prediction models. States that employ these models rely on the resulting predictions to allocate resources in different areas of a city. If the model is biased and, for example, predicts more crime in low-resource areas without this being reflected in reality, it could harm the residents of those areas by imposing unnecessary and excessive policing.

There are several causes for biases in predictive models, three main ones being in crime models:

Metrics commonly employed to evaluate the technical performance of a model do not reveal underlying biases. A model can be 98% accurate, making only 2% errors in its predictions. However, if all of these errors occur consistently in areas inhabited by people from lower socioeconomic strata, a bias may be evident. For this reason, following the work recently presented by Cristian Pulido, Diego Alejandro Hernández, and Francisco Gomez at the Quantil Applied Mathematics seminar, it is imperative to define evaluation metrics different from those traditionally used. For this purpose, a utility function ƒ is established, which can be expressed as follows:

where set C encompasses all protected areas, i.e., areas that could be affected, such as those with low socioeconomic resources. In addition, P represents the probabilistic prediction, while Q represents the simulated crimes. Intuitively, the goal is to minimize the disparity between these two distributions, achieving a model that captures the underlying structure of the crime distributions.

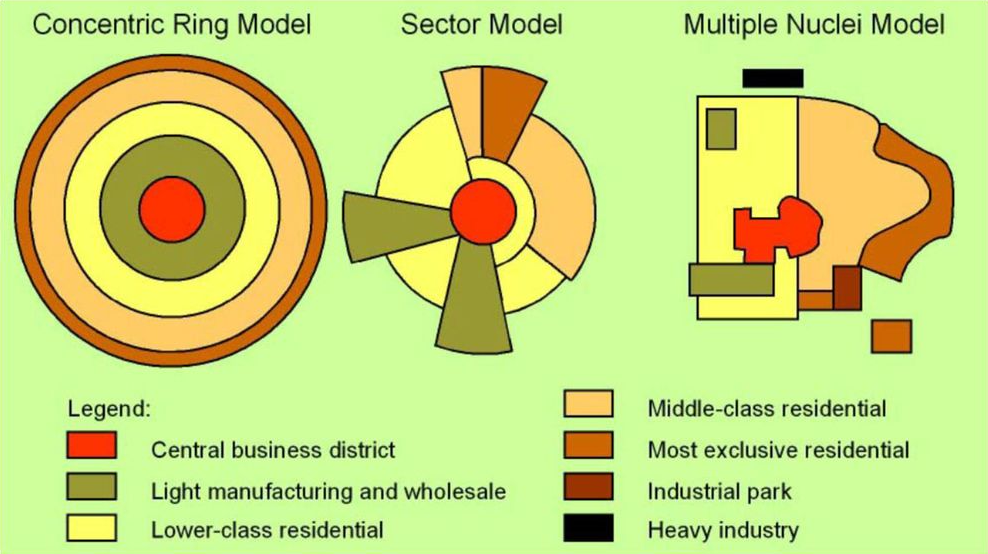

From this value, some fairness metrics such as variance, min-max difference and Gini value are calculated. It is particularly important to analyze the relationship between these fairness metrics and traditional technical performance metrics. This is the objective of Cristian Alejandro Pulido, and Diego Alejandro Hernandez under the direction of Francisco Gomez [2]. For this purpose, 30 scenarios were simulated following the usual population distribution in Latin American cities, which are distributed as a Sector Model:

Three models commonly used in this field were trained from these simulations: NAIVE, KDE and SEPP. For each of these, their technical performance was analyzed by comparing the simulated real distribution with that predicted by means of the earth mover’s distance, and their possible biases based on the variance, max-min distance and Gini of the utility function.

From these experiments, it can be seen that there is a tendency for the best-fit models to have greater injustices, which can be a social problem given that the choice of a model is commonly based solely on these types of traditional metrics. Ignoring fairness metrics may be implicitly biasing and disadvantaging historically discriminated populations.

Although the simulations followed a usual population distribution in Latin America, the artificial data do not always represent reality. In particular, they do not take into account the problems of imbalance and absence of data. This is why the research will continue to demonstrate the impacts on real crime data, and additionally to analyze how underreporting can impact the fairness of the models.

References

[1] Cynthia Dwork, Moritz Hardt, Toniann Pitassi, Omer Reingold y Richard Zemel. Fairness Through Awareness, 2011.

[2] Cristian Pulido, Diego Alejandro Hernández y Francisco Gomez. Análisis sobre la justicia de los modelos más usuales en Seguridad Predictiva. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uCIanZ8jT-4

Get information about Data Science, Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and more.

In the Blog articles, you will find the latest news, publications, studies and articles of current interest.