How should we understand the concept of developing Artificial Intelligence for the common good? This is a key question, which, according to the philosopher Diana Acosta Navas, opens up two central dimensions: one philosophical and the other political.

From the philosophical perspective, Acosta Navas she states: “Because it is common, that qualifier implies that it should benefit all of us, and not just a limited group of people. The question, then, is how to arrive at a definition of what we understand by the common good, in order to design and develop artificial intelligence that truly serves that purpose.”.

One of the most influential approaches has been the utilitarian one, which seeks to maximize the well-being of the greatest number of people. This perspective is linked to the effective altruism movement, which holds that every individual counts equally, with no one being worth more than another (MacAskill, 2017), and that we must also extend this consideration to future generations. From this logic, the prevention of long-term catastrophic risks (such as those that could arise from misaligned AI systems) becomes fundamental, and in this context, initiatives such as Open Philanthropy.

However, this approach presents limitations: by prioritizing the benefit of the majority, it runs the risk of leaving minorities behind. Moreover, the pursuit of maximizing a specific value necessarily involves facing conflicts between different values and making complex trade-offs among them.

Another alternative approach, inspired by Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum, is that of capability-focused Artificial Intelligence. That is, AI based on the substantive freedoms each person must have in order to live and participate in society according to their own choices. This perspective is not limited to the maximization of social utility, but emphasizes how AI affects the opportunities of the most vulnerable. The common good is thus understood as something that includes everyone and not as a benefit for a majority at the expense of marginalized minorities. Even so, from the philosophical perspective, the definition of common good remains open.

From the political perspective, the issue is different. It is no longer about defining what the common good is, but about asking who defines it. Here, the core of the debate is power: who makes the decisions about the development of artificial intelligence, what values are embedded in the systems, and how their impacts are distributed across society.

A useful example for understanding this dimension is the parallel between Elite Philanthropy and the Artificial Intelligence Industry. Elite Philanthropy is driven by the values of its donors, has large-scale impact on matters of public interest, and operates with limited accountability. The criticism is not that individuals use their resources to promote their values, but that by doing so on a large scale, they end up disproportionately influencing collective life.

Foundational Artificial Intelligence models operate in a very similar way. They also incorporate the values of those who develop them, generate wide-reaching social impacts, and do so without sufficient transparency. These values can be explicitly encoded, when developers introduce criteria of justice, privacy, or autonomy in the design, or implicitly, through unrecognized biases and assumptions about who the users are and what their needs may be. Consider, for example, how large language models were initially trained primarily in English, which limits their sensitivity to other linguistic and cultural contexts.

The problem is worsened by the fact that training these models requires immense resources, available only to a few organizations. This further concentrates power and produces a cumulative effect: the same actors who dominate technological development also influence the normative and ethical discussion on artificial intelligence, as is the case with large philanthropic organizations that shape the global agenda.

Frente a esta concentración de poder, se han propuesto mecanismos para democratizar la IA a través de la regulación, la apertura de código y datos, y nuevas formas de gobernanza participativa. Aquí aparece la idea de la alineación deliberativa, que busca superar los límites del diseño participativo tradicional mediante plataformas en las que miles de personas pueden expresar sus puntos de vista, aportar experiencias y votar sobre las propuestas de otros.

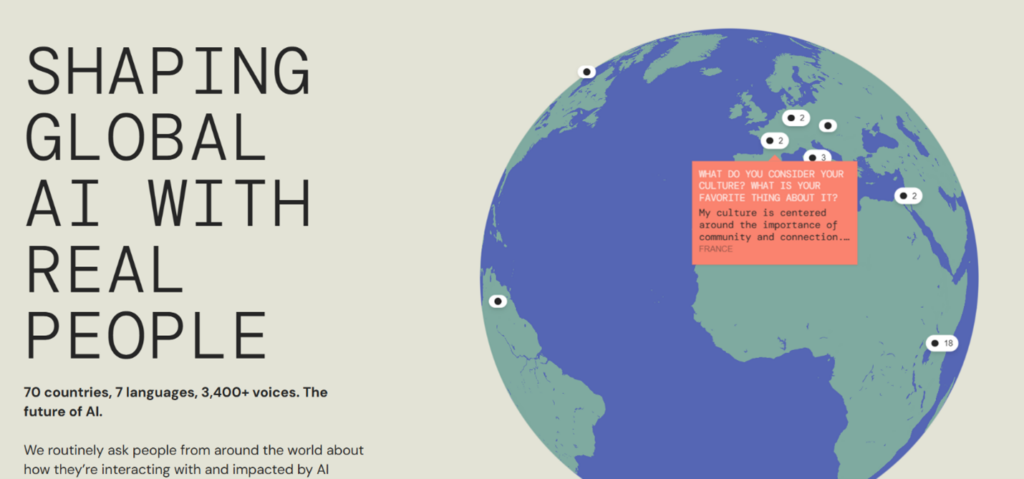

An interesting case is Global Dialogues on AI, which consults citizens in more than 70 countries and in different languages. For example, one of the questions posed was: What kinds of cultural things would you be most worried about losing in a future with advanced AI? One of the most common responses was: Family closeness, native languages, and the solidarity between people that comes from shared cultural experiences and traditions passed down through generations.

The goal is for the answers to these questions to be incorporated into AI design. This type of initiative presents an obvious strength: it generates a wealth of information, offering developers a broad view of the concerns and expectations of communities. However, it also has a clear weakness: the results are not binding and do not include accountability mechanisms. In other words, they help address the information problem, but not the power problem. Deliberative alignment, therefore, represents a step in the right direction, though it is still insufficient.

Several conclusions emerge from this. On the philosophical level, it is crucial to question the conceptions of the common good that guide the development of these technologies and to consider alternatives that place the most vulnerable people at the center. On the political level, it is necessary to critically examine how artificial intelligence systems are redistributing or concentrating power in society. And on the institutional level, deliberative technologies open up possibilities for more democratic participation, but they are still insufficient.

The challenge is great: we need to move toward mechanisms that not only inform, but also distribute power more fairly. The underlying question remains how we can ensure that artificial intelligence, instead of reinforcing dynamics of concentration, becomes a tool that truly contributes to the common good.

Get information about Data Science, Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and more.

In the Blog articles, you will find the latest news, publications, studies and articles of current interest.